The Limburg Memorial, Germany

There are only a few Stalingrad memorials in Germany; the most prominent one is located on the cemetery of Limburg, a town forty miles from Frankfurt. It is a rock of granite bearing the inscription “Stalingrad 1943” and marking the moment when the 110 000 surviving soldiers of the German Sixth Army rendered themselves into Soviet captivity. Only about 6000 of them would return to Germany; the last were freed in 1955. These survivors formed a “Union of Former Stalingrad Fighters,” and they first chose Nuremberg, later Limburg, as the site of their annual meetings, which regularly fell on Volkstrauertag, the National Day of Mourning. These veterans commissioned the “Stalingrad rock” in 1964. Its shape and granite core were to evoke the toughness of the Sixth Army and its soldiers. On top of it rests a large bronze plate holding, chosen to indicate the large number of victims. Hidden below the plate is a crystal shrine containing blood-drenched soil from Stalingrad.

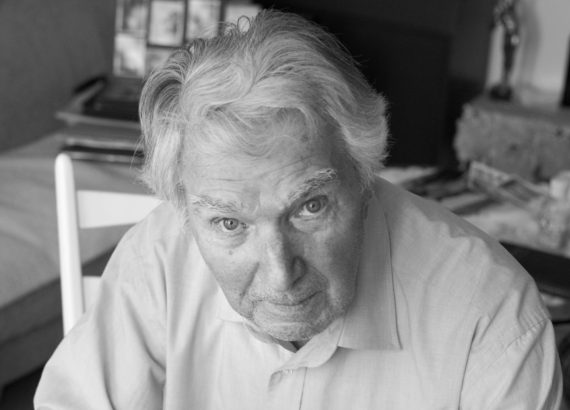

Scores of veterans attended the Limburg meetings during the 1960s and 1970s, each regiment claiming a separate table. Over time, their numbers steadily shrank. When we visited in 2009 (it was here that we first met most of the German survivors who spoke to us for this documentary project), less than twenty veterans were in attendance and they comfortably fit around a single round table. The meeting began with an evening of reminiscences, over coffee, cake, and wine, in an austere room of Limburg’s civic center. The next morning, the veterans visited the cemetery and congregated around the Stalingrad rock. A wreath lay on the ground, bedecked with the flags of the 22 German divisions destroyed by the Red Army between November 1942 and February 1943. Town officials held speeches denouncing past and present wars. A reserve unit of the German armed forces provided a guard of honor while a solo trombone player intoned the sorrowful melody of the traditional German military song, “Ich hatt’ einen Kameraden” (I had a comrade).

2010, the year after our visit, saw the last reunion of Stalingrad survivors in Limburg. Using funds provided by the now defunct veterans’ union, the town of Limburg has pledged to lay a wreath at the Stalingrad rock and to light its plate on every future National Day of Mourning.

In Russia, memorials commemorating the Battle of Stalingrad are legion. The city of Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad) alone boasts more than 235 memorial objects — plates, statues, obelisks, tanks, etc.– and this number does not include the dozens of urban streets that are named after generals, soldiers, and divisions that fought in the battle. A Panorama Museum commemorating the battle stands in the city center, and not far from it, rising from the banks of the Volga river is the Mamayev Hill memorial complex devoted to the Heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad.

Overlooking the complex, which features a Hero Square, a Hall of Fame with an eternal flame, Walls of Ruins, and a Pond of Tears, is a huge female figure with an outstretched sword – a symbol of the Motherland calling on all Soviet citizens to fight for their country’s survival. As the memorial complex makes vividly clear, Soviet public memory of the battle (and post-Soviet Russian memory as well) emphasizes the heroic, and it is an affair of state.

The Volgograd Memorial, Russia

Each year on May 9, thousands of Volgograd residents come to Mamayev Hill to celebrate Victory Day. As in Germany, the number of veterans and eyewitnesses of the Battle of Stalingrad is diminishing rapidly, but unlike in Germany the commemorations continue to draw large crowds. Entire classes of school students are bussed to the celebrations to ensure that the memory of the heroic battle is passed on to future generations.

2010 saw the first public show of the “Faces of Stalingrad” in Volgograd’s Panorama Museum. Two Russian veterans who had been interviewed in their Moscow homes, Anatoli Merezhko and Maria Faustova, traveled to Volgograd to attend the opening ceremony. The next day, Merezhko also visited Mamayev Hill to commemorate his former commander in Stalingrad, Army General Vassily Chuikov, who lies buried at the foot of the Motherland statue.