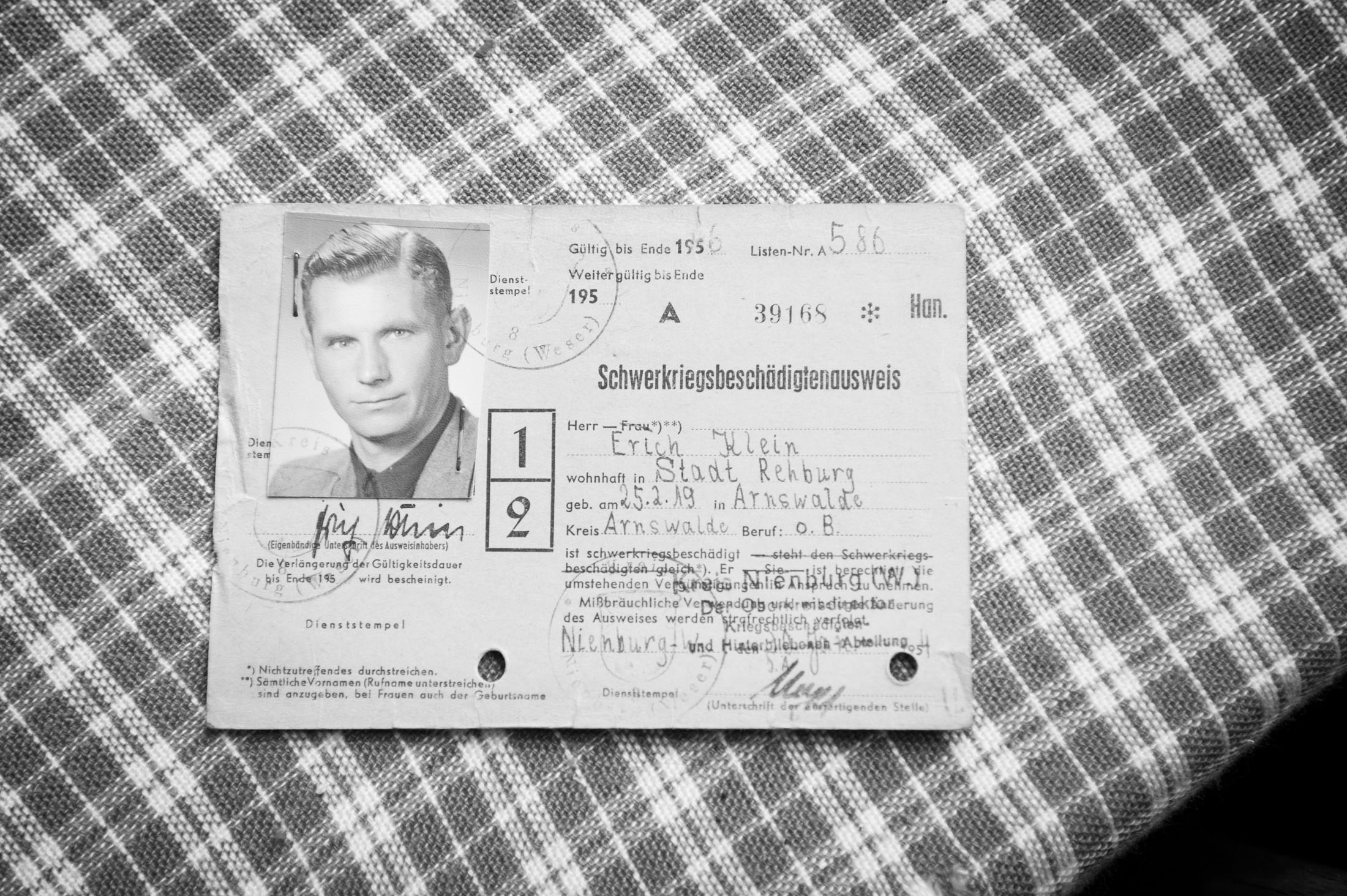

Erich Klein was born into the family of a railroad official in Arnswalde (today in Poland) in 1919. After graduating from the gymnasium in 1937 he was called up for military service. In September 1939 he enlisted as a professional soldier and career officer in the field, and fought with the 60th Infantry Division in France, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union. During the Battle of Stalingrad, the division held the northern outskirts of the city against heavy Soviet attacks from the North.

In early November 1942 Klein received two weeks leave from the front. Upon his return he found the 6th Army surrounded. He was assigned to a panzer army which unsuccessfully tried to break through to the encircled Germans. In January 1945, Battalion Commander Klein (awarded with the German Gold Cross) was taken prisoner by the Red Army in Budapest. He worked for four years in the coalmines of the Don basin.

Accusing him of war crimes, a Soviet military tribunal sentenced him to a 25 year prison term in 1949. Klein was paroled in 1953. He returned to Germany hardly able to walk. In 1959 he married Eva Querner, a pharmacist from Braunschweig, with whom he had two children. In 1962 Klein joined the German Federal Army as major of the reserve. After retiring he became a passionate hobby painter. Klein’s wife died in 1997. His only brother was killed on the Eastern Front.

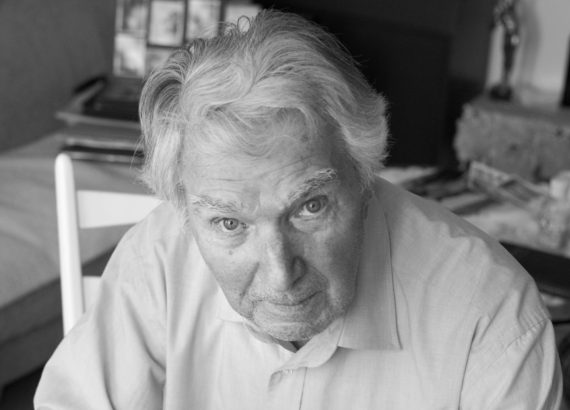

When we met with Erich Klein, first in Limburg and then at his home in Essen, he walked with great difficulty, using a cane. The disability had been with him since his release from the Soviet camps. Klein spoke with a quiet and measured voice, and he sat upright through several hours of interviewing. The long years in captivity, he explained, had taught him how to survive by clinging to “vivid thoughts.” Klein is a passionate hobby painter, and before we left, he showed us the brightly colored paintings and sketches that adorn several rooms of his small rowhouse.