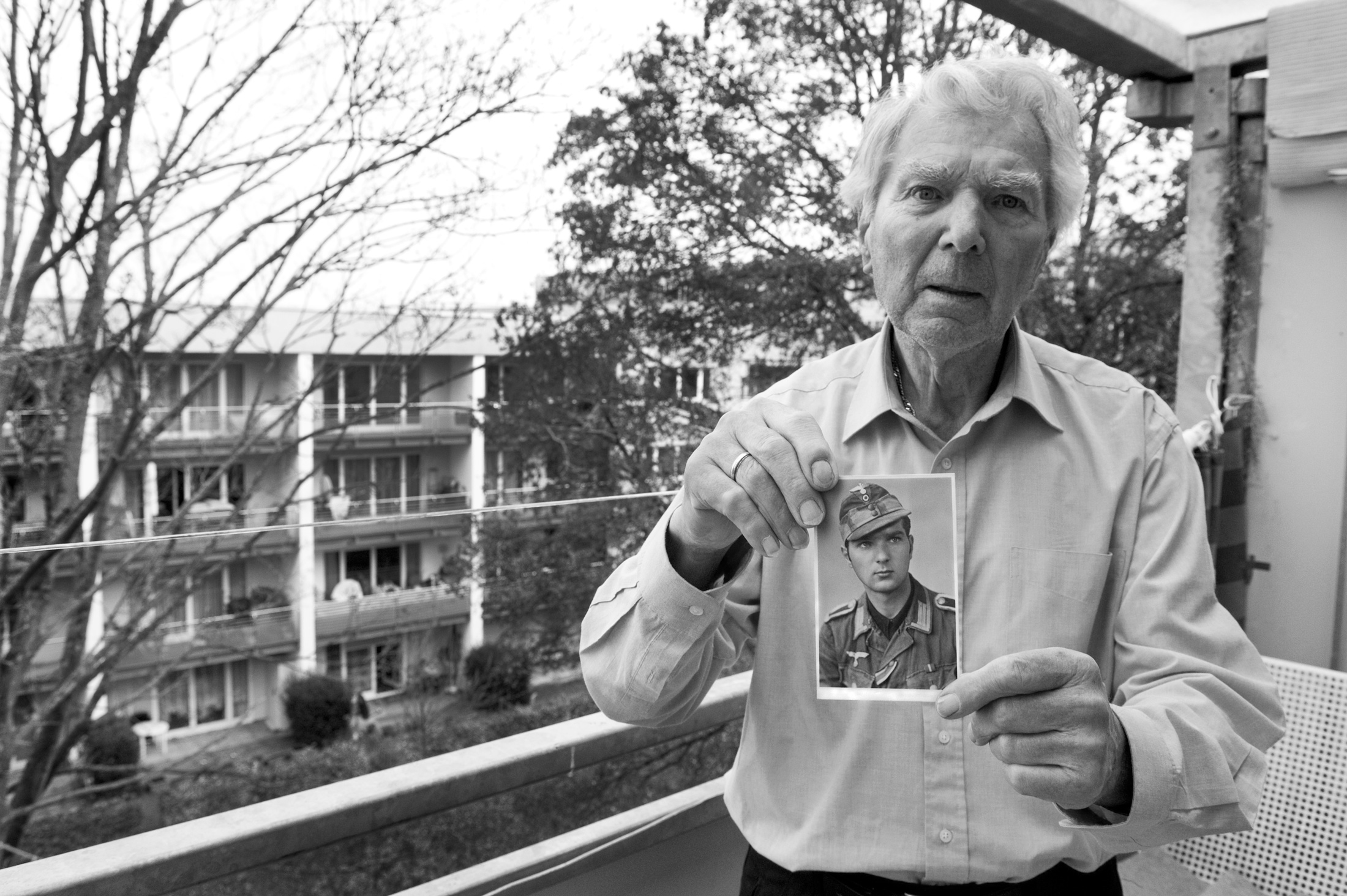

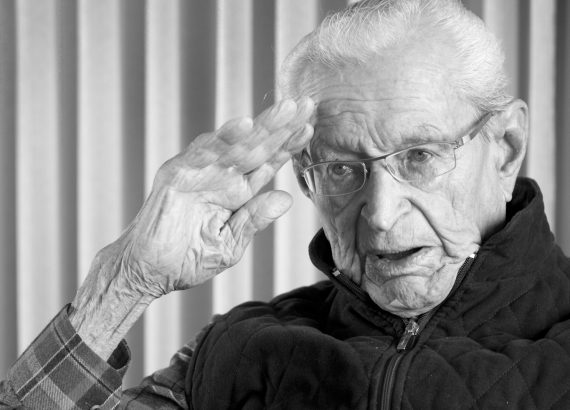

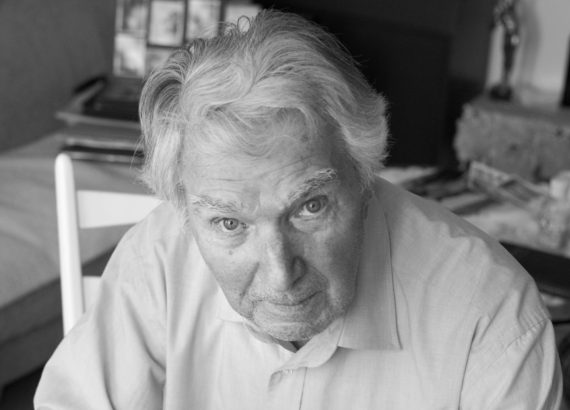

Heinz Huhn was born in 1920 in Rochlitz, Saxony. He was trained as a waiter and then drafted into the army in 1940. Huhn served as gunner in the 94th Infantry Division, which was stationed in France and transferred to the Eastern Front in June 1941. In Stalingrad he took part in the storming of the “Red Barricades” munitions factory. He was sent on home leave on November 8, 1942, just days before the Red Army began to encircle the German troops at Stalingrad. Hurriedly recalled to the front, Huhn joined Panzer Group Hoth, which unsuccessfully tried to break up the encirclement. In March 1943 his unit was deployed to Italy. Huhn was captured by American forces in 1945 and released from captivity in 1946. He later worked as a head waiter in Wiesbaden.

We met Heinz Huhn and his wife (the two had been married for over 50 years, no children) at the Stalingrad memorial service in Limburg, and they spontaneously invited us to their home in Wiesbaden, about an hour away. While Frau Huhn served us delicious gingerbread her husband combed through boxes and drawers in their small, modern apartment to produce a stunning photo collection and other paraphernalia from the war.