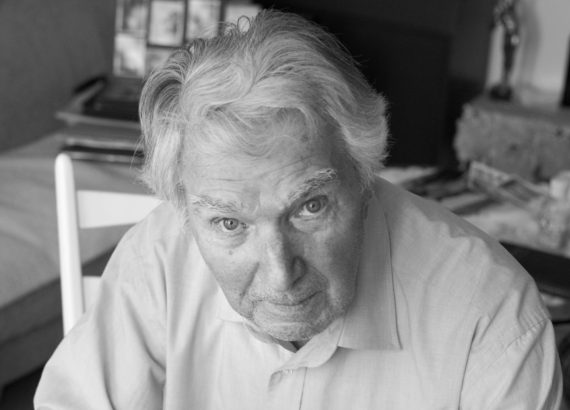

In an interview that I read, you talked about how in the last days of the Stalingrad encirclement 200 or 300 soldiers went out onto the frozen Volga river and collectively blew themselves up? You saw that?

Yes, I was there. They knew that the Russians wanted to kill them. They didn’t want that. So they got together and went onto the Volga, with handgrenades. They made a big hole, three meters wide. I was standing near a barge that was frozen in the river, and I watched. And they roared: “Long live Germany.” And then lit the handgrenades… A huge splash, 10, 15 meter high, pfft. Two, three hundred men – all gone.

What did you think to yourself when you saw that?

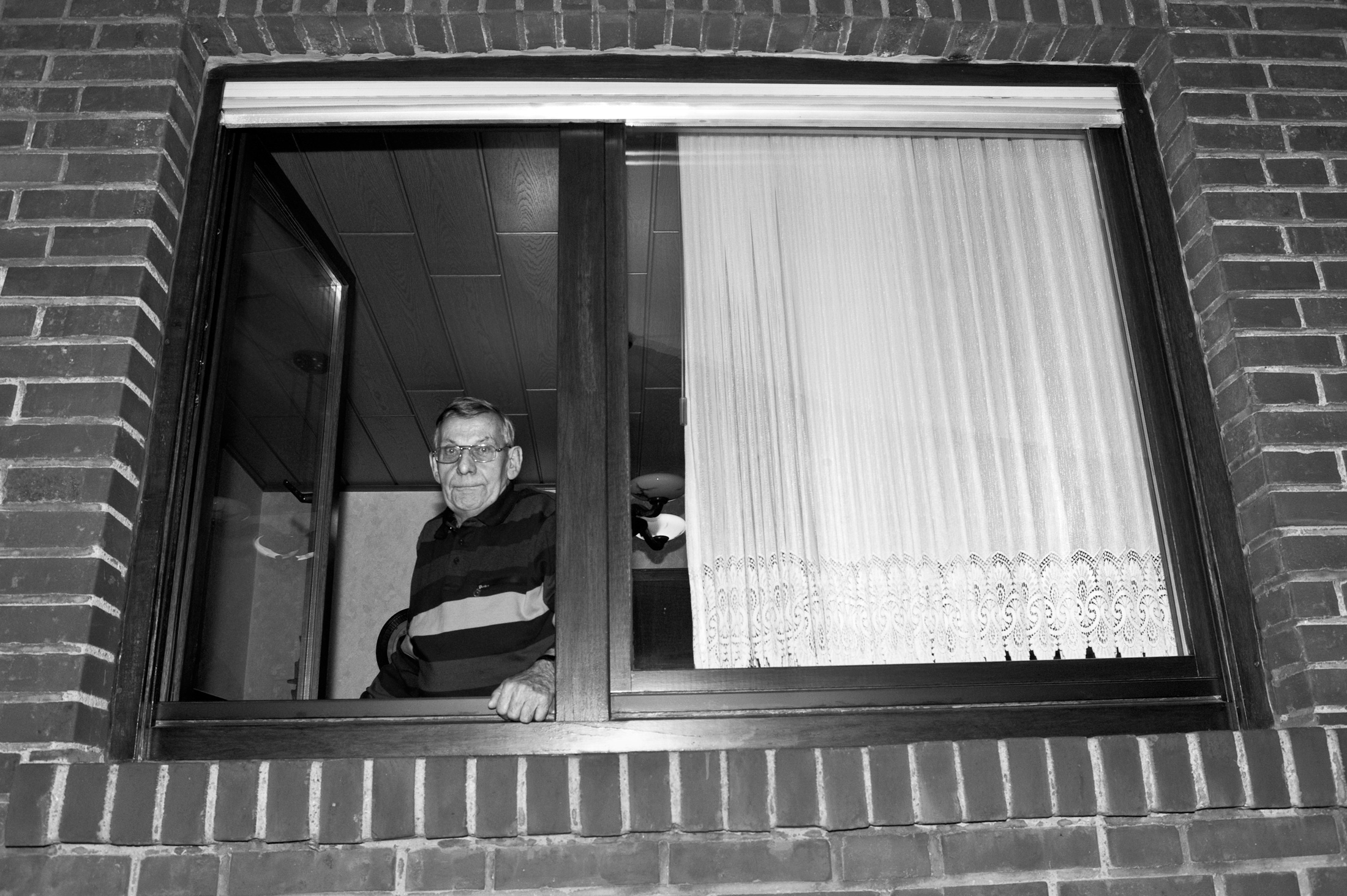

I always thought: I would never do that. No I wouldn’t. They can’t shoot all Stalingrad fighters, all 300,000 men. That would be impossible. The rest of the world wouldn’t allow it. The Americans were in Vladivostok. The world wouldn’t allow it. It’s not possible when there still is a war on. It’s not possible. They could kill a single soldier, but not 300,000 men. And I said to myself: you will not do that. Every evening I told myself that. And I said to the Russians: Posmotri [Russian: “Look here!”]. You have the flesh, but I will take the bones with me back to Germania. I weighed just 64 pounds.

[Scheins tells how he was taken prisoner:]

We were herded onto the square. 6000 men. We were taken to Beketovka. …For fourteen days we lay on the dead. In Beketovka. 45,000 died in 21 days.

So we were in Dubovka. There were another 34,000 dead. We stacked them up: eight men here, eight men there. And in the middle a space so that two horse carts could drive through there. And the people who were lying there, they were all swollen up. Their genitals became swollen. And their eyes and bellies. And we had to throw more dead bodies on top, like this, raz, dva [Russian: “one, two”]. When we did that the Russians enjoyed it. When the dead bodies burst there was a hissing sound. The yellow stuff sprayed all over us. It was warm in June. Then a typhus epidemic broke out, the plague …We stacked up 34,000 there. Dead.