Vera Dmitrievna Bulushova was born in 1921 in the town of Pushkino, near Moscow. She was the oldest of five siblings. In 1941 she volunteered to serve in the Red Army. A brother and a sister followed her example; all three survived the war. She worked as a typist in the military prosecutor’s office. The rifle corps to which she belonged took part in the defense of Stalingrad and was later integrated into Vassily Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army (the re-named 62nd Army). She finished the war in the rank of captain.

In 1946, while working in occupied Germany, Bulushova became married to a reconnaissance officer from her former unit; together they had two children. After the couple returned to Moscow with their first child in 1947 they lived in the apartment of her mother, together with one of Vera’s brothers and his family. Bulushova’s husband died in 1970. Only in 1974 did the Soviet state allocate her an apartment of her own. When we scheduled our interview with Vera Dmitrievna she insisted that we meet at the offices of the Moscow Veterans’ Union, rather than in her modest home.

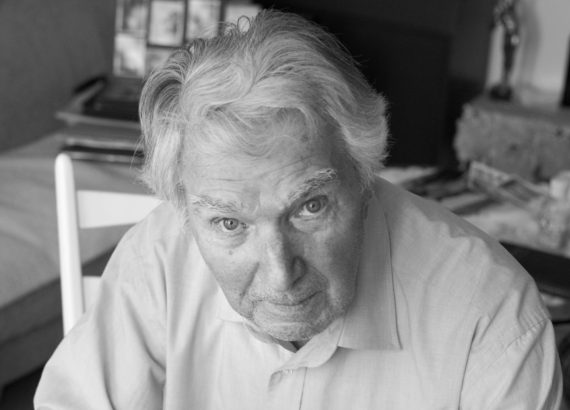

“I just volunteered to do my duty,” Vera Dmitrievna remarked on her war effort during our conversation, “I didn’t marry until after Berlin.” Expressed in her terse words is an understanding, widely shared among Russian war veterans, that state interests unquestionably take precedence over personal desires. This hierarchy emerges vividly in the image that photographer Emma Hanson captured of Bulushova standing below the woven portrait of Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who directed the defense of Stalingrad.