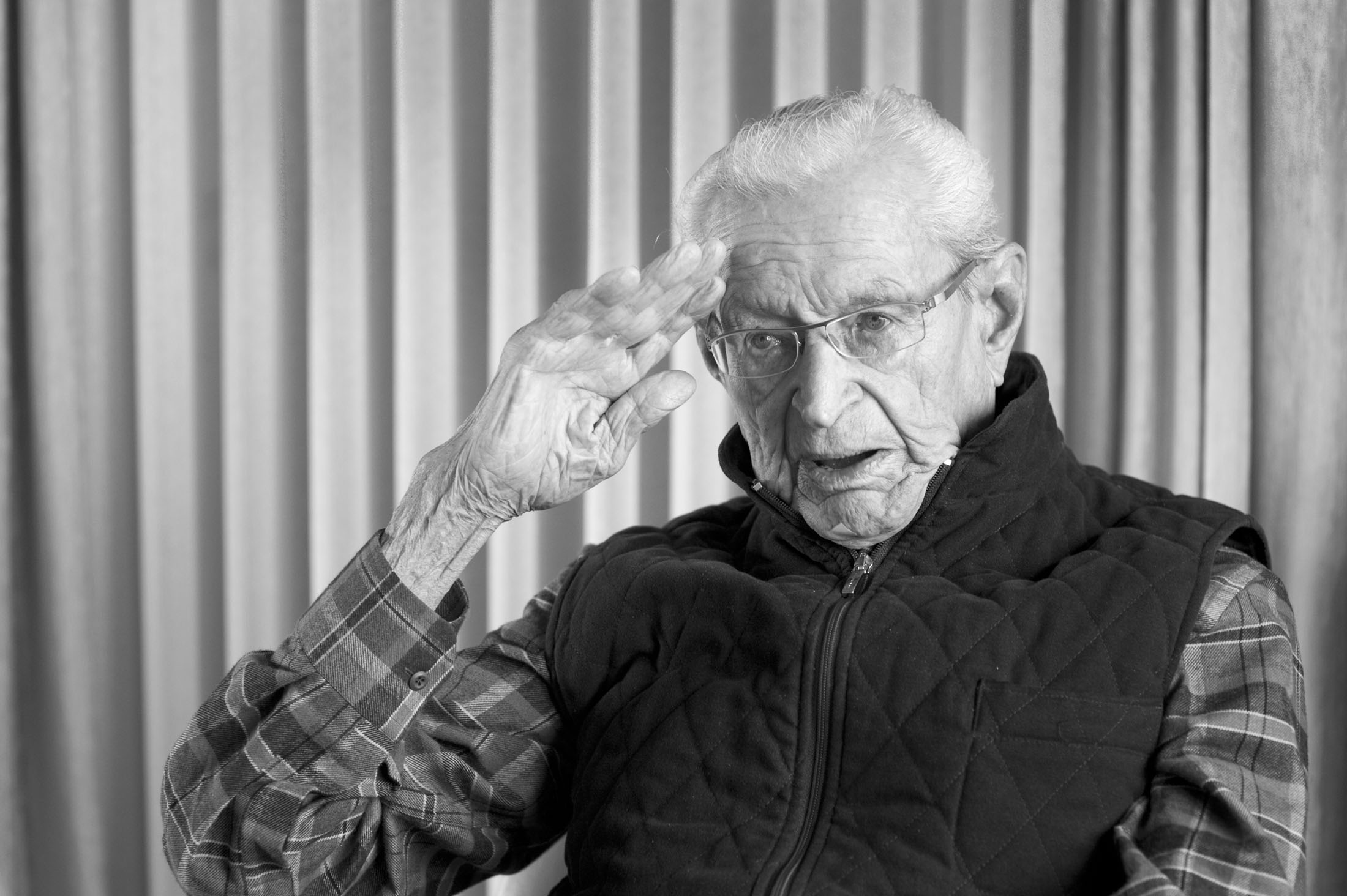

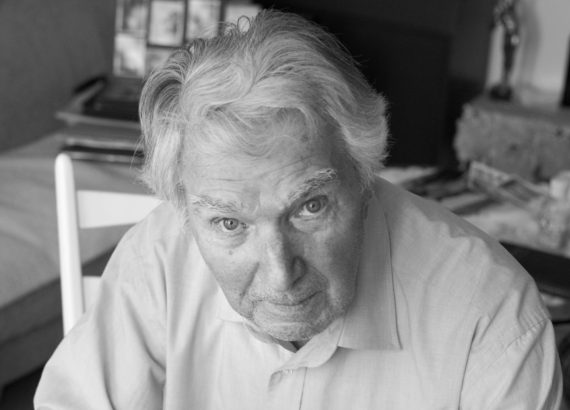

Gerhard Hindenlang was born 1916 in Berlin. A firefighter by profession, he volunteered into the German army in 1939. He was a First Lieutenant in the 71st Infantry Division that spearheaded the attack into Stalingrad in September 1942. Promoted to captain in January 1943, Hindenlang became adjutant to his regiment’s commander, Friedrich Roske, who in turn was made divisional commander on January 26. All surviving soldiers of the 71st Infantry Division were taken prisoner by the Red Army on January 31, 1943.

Hindenlang returned from Soviet captivity in 1952. He settled in Hannover where he married and started a business career. Later he enlisted as a battalion commander in the German Federal Army.

When we sat down with Hindenlang in his modern apartment in Walldorf, near Heidelberg, he zoomed in on the last days of the German defense of Stalingrad, which he spent in the basement of the city’s central department store, together with his divisional commander and Army Commander Friedrich Paulus.

The different characters and fates of Roske and Paulus, and Hindenlang’s relationship with them, are central themes in his story.