That is to say, they respected the bayonet?

They sure did. And the entrenching spade too. Because once that one is within reaching distance of the head it’ll take it right off.

Germans didn’t fight with spades?

They had submachine guns… They hardly even had any bayonets. They had carbines, knives: dagger-like but short. And our bayonet was impressive in size. …

The Germans had those storm groups, but their resolve was far from ours. Our last soldier standing would still fight to his last bullet. But they were always in groups. Alone a German wouldn’t fight. And before the Volga or the Don they were used to advancing: first the planes would bomb, then the artillery, then the tanks, and only after them the infantry. That was the mass approach they kept at Stalingrad, too. But there they had to deal with high-rise buildings, solid brick, and all their “sea wave”, powerful as it was, broke down into rivulets. The buildings, like wave-breakers, broke them; they had to take the streets where they were shot at from every building. And, what’s important is that the tanks were afraid to go deeper. And the infantry wouldn’t advance without them. And it turned out this way: they’d do the artillery preparation… What would give us a chance is the strategy of closing in, introduced by Vassily Ivanovich [Chuikov]: cutting the distance to a minimum.

The thing was that no-man’s-land would be only 30-40 meters. Close enough for a hand grenade exchange. And the German one wouldn’t always reach the target. Say, a German lobs his grenade with a long wooden handle. It has a 9 second fuse. It drops into our trench, our guy grabs it, throws it back and it explodes there. But on our grenades there were 4-5 second fuses. So our defensive or offensive grenades would go off in enemy territory. But theirs, with a twice longer fuse, would often be lobbed back.

You mentioned that during the retreat many had run away. Does that mean that the blocking detachments (introduced by Stalin’s Order # 227 in July 1942) weren’t performing their function?

Well, during the entire retreat (I entered combat 120 kilometers away from the Volga, to the west of Stalingrad) I never had to deal with blocking detachments. In the first place, they’ve made up too many stories about those units. In the second place, they were only beginning to create them at the time – the order mandating their creation appeared only on July 28. At first they were being created only from the army cadres – army barrier troops. Through the counterintelligence department they followed the orders of the commander-in-chief of the military council. Plus, at first they were formed from combat officers themselves – those with experience. Such an officer wouldn’t shoot his own soldiers willy-nilly.

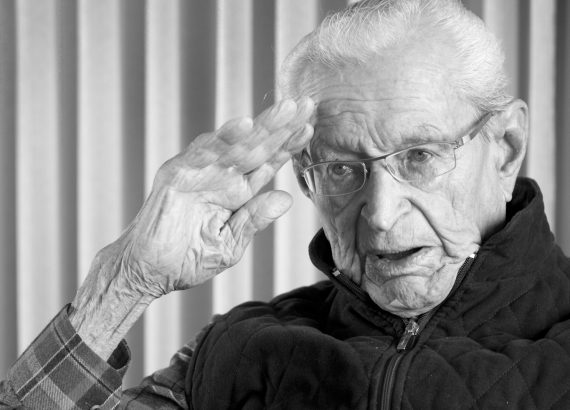

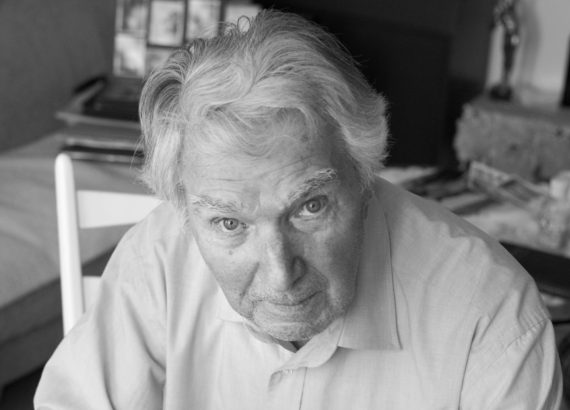

October [1942] was the turning point in my service. We had sustained colossal casualties in the latest fighting and the remnants of the cadets’ regiment had been taken across the Volga in mid-September. And at that time they graduated those cadets who had survived – in the rank of lieutenant. … We – the main body of the college, platoon and company commanders with more serious military training – were assigned to different posts in various corps and headquarters of the 62nd Army.

After a concussion I was stuttering. So, imagine I’m reporting [to Army Chief of Staff General Nikolai Krylov] with a stutter, when he suddenly interrupts me and asks:

“Do you sing?” I’m reporting about the situation at the Stalingrad tractor plant where fighting is horrific, and he goes:

“Do you sing?” I’m taken aback, I tell him that I used to sing while fishing with the guys in the evening. And he says:

“Why don’t you try speaking in a sing-song manner: it will be easier to report”.

For me, who at some point commanded 100 boys (our cadets were 17 – 19 – 20 years old) in full view of everybody (and with the world looking on, as they say, death is not half as bad) being here [in Stalingrad] was a big change: to act alone or with just one or two submachine gunners, depending on where I was heading. By and large I was on my own. During one such trip to Smekhotvorov’s [193rd Rifles] Division we were returning from the frontline – I was accompanied by a submachine gunner. We were somewhere in the factory district, where there were a lot of train tracks and damaged freight trains inside the plants: empty ones or the ones that had been loaded with coal and ore at some point. So we are lost in that labyrinth, we see some people scurrying nearby, identify them as Germans. I tell my guy to take cover behind a wheel and protect the rear. Take a position myself… They open up on us, we fire back. I feel they are not firing too accurately. They must have determined that it’s just two of us and decided to take us alive. They are getting closer and closer… And I have my Party membership card in my pocket and my senior lieutenant’s ID. If I’m captured – a communist – I’m done for… I have a grenade prepared… Just about to set it off [to kill himself]. And at the very last moment, when it’s some 50-60 meters to the Germans, I hear “What the hell! Goddamn it!” “Don’t shoot at those” Turns out it’s our own sailors who had engaged [the Germans] from the rear.

This is why I thought that death could be glorious when I commanded a company, always marching in the front line:

“Onward! For the Motherland! For Stalin!” There, to die wasn’t terrible, but here – you don’t even know on which list they’ll put your name down: missing in action, captured, killed … only God knows… If killed, will they find your papers? Such was the attitude… Although I never thought about whether I’d live to see tomorrow or the day after tomorrow. Everyone knew it could all end at any place, at any moment. And so I’m thinking:

“I’m gonna set off the grenade…”. And tell my submachine gunner:

“If something happens to me, fall back. If you make it, tell them we fought here”.

There were plenty of non-standard situations, too. There were times we’d swap items with the Germans: we, sitting on lower floors, would send them water in a pot upstairs, and they from the second or third floor would send us cigarettes and watches. Yeah, we’d swap with them. A fifteen-minute armistice. Drove political officers crazy with this informal fraternization. Imagine that!