Some of the veterans willingly shared their letters and photo collections from the war, but the personal encounters made me aware of something he had initially overlooked: the enduring presence of the war in their lives, and the strikingly different ways in which Germans and Russians engage with war memories. The battle may lie almost seventy years in the past, yet traces of it are powerfully etched into the bodies, thoughts, and feelings of its survivors. Here was a domain of the war experience that no archive could reveal.

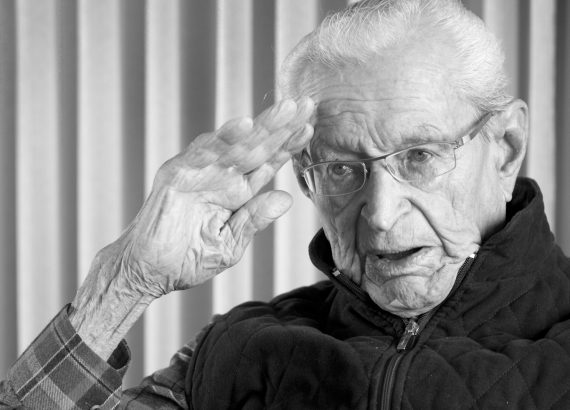

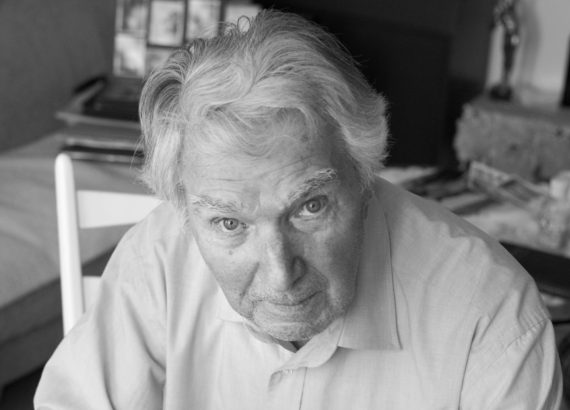

This experience pervades the veterans’ homes: it whispers through the pictures and artifacts from the war that hang on walls or are safely stowed away; it holds itself in the straight backs and courteous manners of former officers; it flares up in the scarred faces and limbs of wounded soldiers; and it lives on in the veterans’ simple gestures of sorrow and joy, pride and shame.

To fully capture the war’s complex, enduring presence required a camera in addition to a tape recorder. Emma Dodge Hanson, an accomplished photographer and a friend, kindly accompanied me on my visits. In the short span of two weeks, Emma and I traveled to Moscow and a range of cities, towns, and villages in Germany, where we met nearly twenty veterans in their homes. Emma has a singular ability to record people when they are at ease with themselves, nearly oblivious to the photographer’s presence. Shot with natural light whenever possible, the pictures capture the gleam reflected in the subjects’ eyes. The richly nuanced images bring out the fine wrinkles and furrows that grow deeper as the veterans laugh, cry, or mourn. Studied together, the hours of taped testimony and the stream of photographs captured portray the veterans residing in their recollections, as real to them as the furniture surrounding them.

Emma and I were invited into homes both modest and ornate, we spoke with decorated war veterans as well as simple soldiers, and we watched their hosts celebrate or silently grieve. We recorded some men changing into parade uniforms that looked huge on their shrunken bodies, and we held in our hands the small objects that had sustained survivors through war and the prison camps. In essence, we observed the workings of two contrasting cultures of memory: the haunting shadows of loss and defeat in Germany, and the broad sense of national pride and sacrifice in Russia. Uniforms and medals were much more widespread on the Soviet than the German side, and Russian women claimed a more active role for themselves as participants in the war. In German storytelling, Stalingrad often marks a traumatic break in the person’s biography. Russian veterans, by contrast, tend to underscore the positive aspect of their self-realization in war, even as they confide memories of painful personal loss.

Soon the veterans of Stalingrad will no longer be able to discuss the war and how it shaped their lives. This makes it imperative to record and compare their faces and voices now. Of course, the manner in which participants reflect on the battle nearly seventy years later should not be equated with the terms in which these individuals experienced the war in 1942 or 1943. Each individual’s experience is a linguistic construction, socially shared and historically unstable.

Their recollection of World War II thus inherently evolves over time, reflecting changing social attitudes toward the war. Yet this shifting narrative can provide us with crucial insights: both about Stalingrad itself and the vacillating nature of cultural memory.

(Source: Jochen Hellbeck, “Facing Stalingrad: One Battle Births Two Contrasting Cultures of Memory,” Berlin Journal 21. Fall 2011)