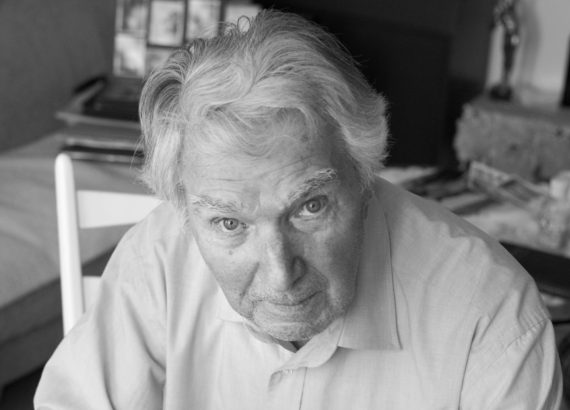

Franz Schieke was born in 1922 in Hecklingen, near Magdeburg. He was drafted into labor service in 1941 and sent to the Eastern Front. In 1942 he became a soldier and served as lance corporal and orderly to Captain Münchin the 71st Infantry Division. While Captain Münch was flown out of Stalingrad on January 22, 1943, his orderly fell into the hands of the Red Army a few days later. After seven years in Soviet captivity He Schieke returned to East Germany (GDR) where he joined the communist party (SED) and worked in the GDR’s Ministry of the Interior. When the Berlin Wall came down and the reformed SED agreed to the unification of Germany Schieke left the party in protest. The merging of the two Germanies enabled Schieke to search for his erstwhile commander Münch who lived in the West. Sometime in the 1990s Schieke located Münch’s phone number and rang him up.

During our meeting with Schieke in his modest apartment in Pankow, a district in Berlin’s North-East, he mainly spoke about two themes – his relationship with Münch, and the political bias with which he believes Stalingrad is remembered by West Germans to this day. Schieke emphatically presented his life history as a corrective to this bias.