The Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad marked a turned pointing in World War II. For six months, two massive military forces, each instructed by their respective leader not to cede an inch to the enemy, fought for control of the city that bore the Soviet dictator’s name. The battle ended with the encirclement and destruction of an entire German field army.

It was the largest military defeat in Germany’s history so far—and, in the immediate aftershock, the writing on the wall for clear-eyed German observers. For the Soviet Union, Stalingrad represented its hitherto greatest victory over the German invaders. It shifted the war’s momentum decidedly in favor of the Red Army; after Stalingrad, its divisions would push steadily westward, their sights set on Berlin.

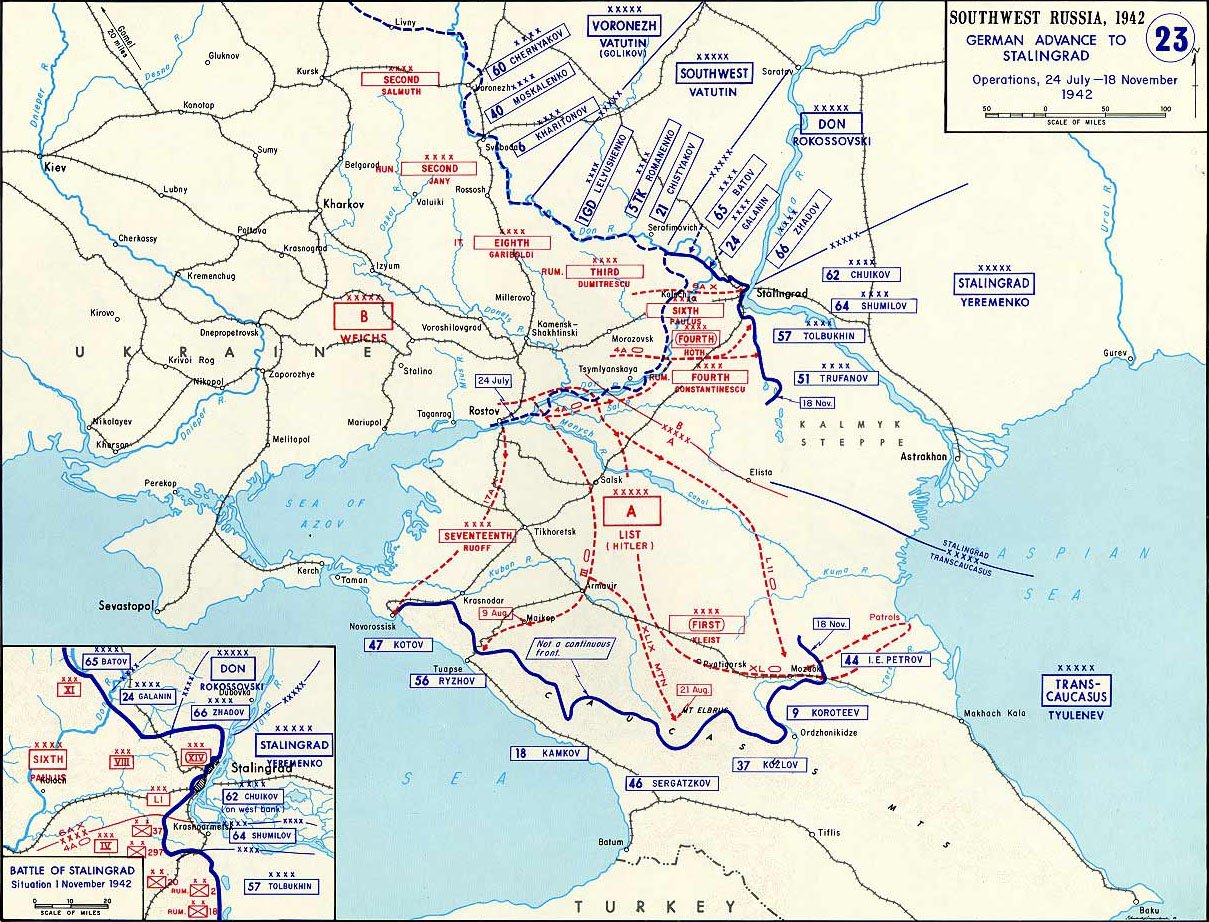

After German advances on Leningrad, Moscow, and Sevastopol came to a standstill in the fall of 1941 and the Soviets launched their winter counterattacks, Hitler started planning a sweeping offensive for the following summer codenamed Operation Blue. It began on June 28, 1942 with a major assault along the Russian-Ukrainian front to take control of the region’s strategically important natural resources—the coalmines of the Donets Basin and the oilfields outside Maykop, Grozny, and Baku. The German panzer and motorized infantry divisions gained ground quickly, but the pincer tactics they employed often missed their mark: whenever faced with encirclement, the Red Army divisions broke into rapid retreat. Hitler, under the assumption that the enemy troops had already dispersed, divided Army Group South into two parts: Army Group A, which was ordered to push forward toward the Caucasus, and Army Group B, which was to head northeast and secure the flanks. The spearhead of Army Group B was the Sixth Army, under the command of General Friedrich Paulus. Its mission was to capture the city of Stalingrad, a key center for industry and weapons manufacturing on the Volga River.

By July of 1942, the gravity of the situation—as even the quickest glance at the map made plain—had become apparent to many Soviet citizens, and many believed that the war had already been decided. The writer Vasily Grossman noted in his diary, “The war in the south, on the lower reaches of the Volga, gives one a feeling of a knife driven deep.” The regime reacted with severe measures. After Rostov-on-Don fell into German hands with little resistance, Stalin issued order No. 227, notorious for its line “Not one step back!” Henceforth, anyone who retreated from the enemy without an express order to do so would be branded a traitor to the fatherland and subjected to a military tribunal; deserters faced summary execution. The draconian edict was first enforced at the Battle of Stalingrad. The city extended like a ribbon twenty-five miles along the western bank of the Volga. Here “Not one step back!” meant that the river was the furthest point of retreat for the city’s defenders.

From the outset of the battle, Soviet leaders impressed on soldiers the symbolic significance of Stalingrad. It was the place where Stalin had staved off the enemies of the Soviet system during the Russian Civil War. Losing Stalingrad to the Germans would damage the myth surrounding the city and its eponymous hero, and had to be prevented by all means. For this reason, too, the city assumed crucial importance to Hitler. Banking on the psychological blow a defeat would deliver to Stalin, he framed it early on as a battle between two opposing worldviews. On August 20, 1942 Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary that the Führer “has made the city a special priority. …Not one stone will be left on another.”

At the western bend of the Don curve, still quite a ways from Stalingrad, German forces encountered heavy resistance from the Soviet 62nd Army. The Germans took 57,000 prisoners and crossed the Don on August 21. By the twenty-third, the first German panzers reached the Volga, some forty miles away, and barred access to Stalingrad from the north. The news set off alarms in Moscow. Three days later, Stalin appointed General Georgy Zhukov deputy supreme commander of the Red Army and made him responsible for the city’s defense.

When war broke out, the population of Stalingrad was just under half a million. Initially, Stalingrad had been considered a safe haven far behind the front line, and by the summer of 1943 it was overfilled with refuges. The city’s administrators implored Stalin to permit the evacuation of factories and civilians—to no avail. Lazar Brontman, a Pravda correspondent who was present during these discussions, recorded in his diary “how the boss [Stalin] responded with a glum expression: ‘Where should they be evacuated? The city must be held. That’s final!’ And pounded his fist on the table.” Only after German bombers had laid waste to the city did Stalin allow women and children to leave.

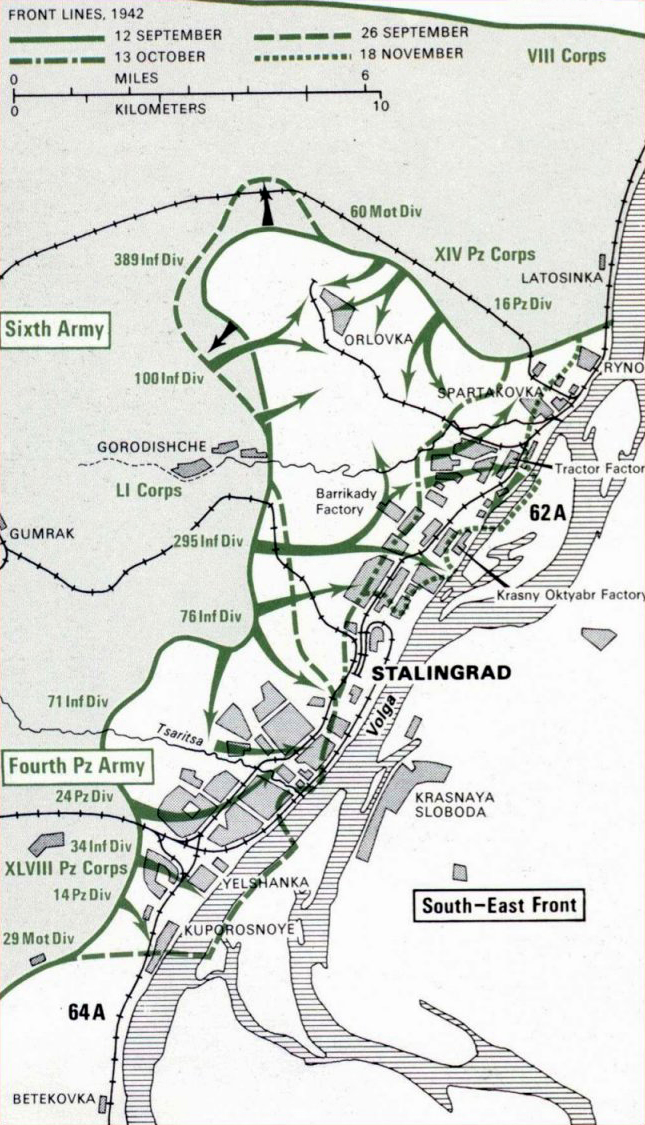

After two weeks of bombing, the German troops began their storm of Stalingrad. On September 14, a regiment broke through the inner city and reached the Volga. In the heavy street fighting that ensued over the following weeks, the Germans managed to push the soldiers of the 62nd Army back to the banks of the Volga. Once the Wehrmacht’s shock troops had cleared a path, the German occupation authority set up headquarters, began executing communists and Jews, and prepared the deportation of the civilian population. On the other side, the Soviet defenders, dug in on the Volga’s steep western bank, held no more than a few bridgeheads. They received supplies, soldiers, and weapons by boat and cover from artillery positions on the east side of the Volga. The 62nd Army in Stalingrad was part of the Southeastern Front, commanded by General Andrey Yeryomenko, and which consisted of the 64th, 57th, and 51st Armies, the 8th Air Army, and the ships and sailors of the Volga fleet, all stationed to south of the city; and of the 1st Guards Army and the 24th and 66th Armies, located to the north and northwest. The latter cluster tried multiple times in September to break through Germany’s northern barricade and reach the city’s defenders but never succeeded.

The Soviet plan for a comprehensive counteroffensive took shape in mid-September during the critical phase of the defense of Stalingrad. In a meeting with Stalin, Zhukov and Aleksandr Vasilevsky, the Chief of the General Staff of the Soviet Armed Forces, proposed an operation that adopted the German strategy of deep double envelopment. Over the next two months, preparations were made: another formation (the Southwestern Front), under the command of General Nikolai Vatutin, secretly moved to a position at the upper part of the Don; meanwhile the armies fighting in Stalingrad (since the end of September divided into two fronts: the Don Front, under the command of Lieutenant-General Konstantin Rokossovsky, and the Stalingrad Front, under the command of Yeryomenko) received reinforcements of soldiers and equipment. These maneuvers did not go undetected by the Germans, but intelligence officers, believing that the Soviet Union’s reserves of materials and soldiers had been exhausted, attached no special importance to them.

After a number of concentrated drives in October, the 6th Army still had not taken complete control of Stalingrad. German observers looked to explain the enemy’s unexpectedly bitter resistance. The lead article in the October 29, 1942, edition of the official SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps began with an assessment of Soviet morale: “The Bolshevists attack until total exhaustion, and defend themselves until the physical extermination of the last man and weapon. …Sometimes the individual will fight beyond the point considered humanly possible.” Everything the soldiers of the Wehrmacht had experienced in their campaigns in Europe and North Africa was like “a child’s game compared with the elementary event of war in the East.” The article accounted for this difference by evoking the laws of racial biology. The Soviet soldiers belonged to another “race”; they originated from a “baser, dim-witted humanity” unable “to recognize the meaning and value of life.” Due to this purported absence of human qualities, the soldiers of the Red Army were though to fight with a disregard for death that was foreign to culturally superior Europeans. The article concluded by depicting the threat for Europe contained in the “power of this unleashed inferior race,” and made the Battle of Stalingrad into a question of world historical destiny. “It is up to us to decide whether we remain human beings at all.”

On November 19, 1942, the Red Army finally began its counteroffensive, known as Operation Uranus, with a contingent of over one million soldiers. Motorized divisions advanced through the Romanian-controlled Don heights 150 kilometers west of Stalingrad. On November 24, the Soviet tank vanguard joined forces with Yeryomenko’s tank divisions, which had begun to push westward from south of Stalingrad four days earlier. The Germans and their allies were surrounded, trapped in what they referred to as a Kessel, or cauldron.

The 6th Army command deliberated whether to attempt a breakout, but Hitler ordered “Fortress Stalingrad” to be held at all costs. He called for an airbridge supplying the soldiers in the Kessel with food and munitions. This was not the first time Hitler had tried this approach. When, in December 1941, the Red Army began its counteroffensive outside Moscow, Hitler, who had just named himself Army Supreme Commander, issued an order that forbade German troops any backward movement under the threat of severe punishment. Shrouding himself in the mystique of the strong-willed military leader whose job was to embolden his generals whenever they succumbed to their “neurasthenia” and “pessimism,” Hitler credited his decision with preventing the collapse of the Eastern Front despite the strong attacks from the Red Army in the ensuing weeks. In January 1942, Soviet forces nevertheless managed to encircle six German divisions, consisting of almost 100,000 soldiers, further North near Demyansk at Lake Ilmen. Hitler responded by sending planes to drop supplies for the encircled troops. This continued for two months until a relief force broke through the Demyansk Pocket from the outside at the end of March. It was this successful precedent that General Paulus thought of when he sought to assuage the trapped men of the 6th army by concluding his November 27th order with the slogan, “Hold on! The Führer will get us out!”

But weather and heavy shelling hampered the Stalingrad airlift; the 300,000 encircled soldiers began to suffer visibly from shortages in food and munitions. General Erich von Manstein launched Operation Winter Storm (December 12–23, 1942) in an effort to force open the encirclement with a panzer advance from the southwest, but it became bogged down midway, encountering strong Soviet resistance. In the meantime the Red Army had initiated an offensive on the Don further to the west known as Little Saturn. Its objective was to break through to Rostov in the south, stymieing Germany’s relief force, and cutting off the entire army group, along with the 400,000 troops stationed in the Caucasus. The offensive succeeded in part: it forced Manstein to abort Operation Winter Storm, but he was still able to protect the army in the Caucasus from strangulation.

At the end of November Soviet leaders began a massive propaganda campaign to persuade the Germans and their allies to surrender. Soviet aircraft dropped hundreds of thousands of leaflets written in German, Romanian, and Italian, describing the hopelessness of the situation. A delegation of German communist exiles in Moscow travelled to Stalingrad and broadcast political messages over loudspeaker, but their efforts to prevail upon their countrymen on the other side of the front line brought no results. On January 6, two weeks after Manstein aborted his relief operation, General Rokossovsky offered Paulus terms for an honorable surrender. Under intense pressure from Hitler, the 6th Army commander ignored the deal.

The Soviets’ final push to crush the encircled German troops, codenamed Operation Ring, began on January 10. From the West, soldiers on the Don Front drove the enemy gradually back into the city. At the same time, the 62nd Army intensified its attacks from the banks of the Volga, and on January 26 it joined the Don Front at Mamayev Kurgan, a strategic elevation south of the city’s industrial district and the scene of fierce fighting for months. The Soviets cut the Germans into two encirclements, one in the north, the other in the south. General Paulus, repeatedly forced to give up his quarters as the Red Army closed in, sought refuge for himself and his staff on January 26 with the 71st Infantry Division, the first unit to have reached the Volga at Stalingrad and whose commanders were now headquartered beneath the department store on the Square of the Fallen Soldiers. On January 30, the tenth anniversary of the day the Nazis assumed power, Hermann Göring held a radio address that reached soldiers in Stalingrad. Göring compared the Germans in Stalingrad to the heroes of The Song of the Nibelungs. Like those who “fought to the last man” during an “unmatched battle in a hall of fire and flame,” the Germans in Stalingrad would fight – would have to fight – “for a people who can fight like this must win.” On the night of January 31, Paulus received a signal from Führer headquarters saying that he had been promoted to field marshal. Everyone involved understood the message: never before had a German field marshal been taken prisoner; if Paulus wanted honor, he had to kill himself. He chose to defy his Führer.

In the morning hours of January 31, Soviet soldiers of the 64th Army surrounded the Square of the Fallen Soldiers. A German officer emerged with a white flag and offered terms of surrender. A group of Red Army soldiers were escorted into the basement below the department store, where Paulus’s army staff was assembled. (A detailed description of this meeting can be found in this book.) Several hours later, the German soldiers in the south Kessel threw down their weapons. In the tractor factory in the north Kessel, soldiers continued fighting until 2 February. By then, 60,000 German soldiers had died in the Stalingrad since the Soviet counteroffensive began. 113,000 German and Romanian survivors were taken prisoner, many of them injured or exhausted. All in all, the battle and the subsequent imprisonment cost 295,000 German lives (190,000 on the battlefield, 105,000 in captivity). On the Soviet side, conservative estimates place the number of dead at 479,000, though one scholar has put the death toll at over a million.

Nazi leaders responded to the defeat of the 6th Army by ramping up their propaganda and mass mobilization efforts. The sacrifice in Stalingrad, they believed, would motivate German soldiers in the fight to stem the “red tide” now moving westward. No sooner had the three-day period of national mourning ended than Joseph Goebbels delivered his total war speech, met with frenzied applause from an audience of party loyalists. With the Red Army threatening to cross into Europe, the specter of “Bolshevik hordes” from “Asia” long invoked by Nazi ideologists was a real possibility; for the terrified population, fighting on seemed like the only way out – and that’s what happened, with greater intensity than before, as the war waged for two more years.

The Soviet side also intensified the political pressure. The captured German generals and officers were placed in a special camp and called on to publically renounce Hitler. The army elites, with Paulus at the forefront, were to be representatives of a new Soviet-friendly Germany one day. Most other prisoners were placed in the normal work camps, where they received little to eat and poor medical care. By July 1943, three quarters of all German prisoners in Soviet captivity had died.

When Red Army soldiers recaptured the city, they counted 7,655 civilian survivors. As the cleanup began, the Soviets discovered mass graves filled with the residents the German occupants had shot or hung. Several thousand captured Germans were put to work in February 1943, clearing bodies and defusing bombs and mines. Eventually they would help rebuild the city.

Source: Jochen Hellbeck, Stalingrad: The City that Defeated the Third Reich (New York: PublicAffairs, April 2015).